AI and Campaign Finance

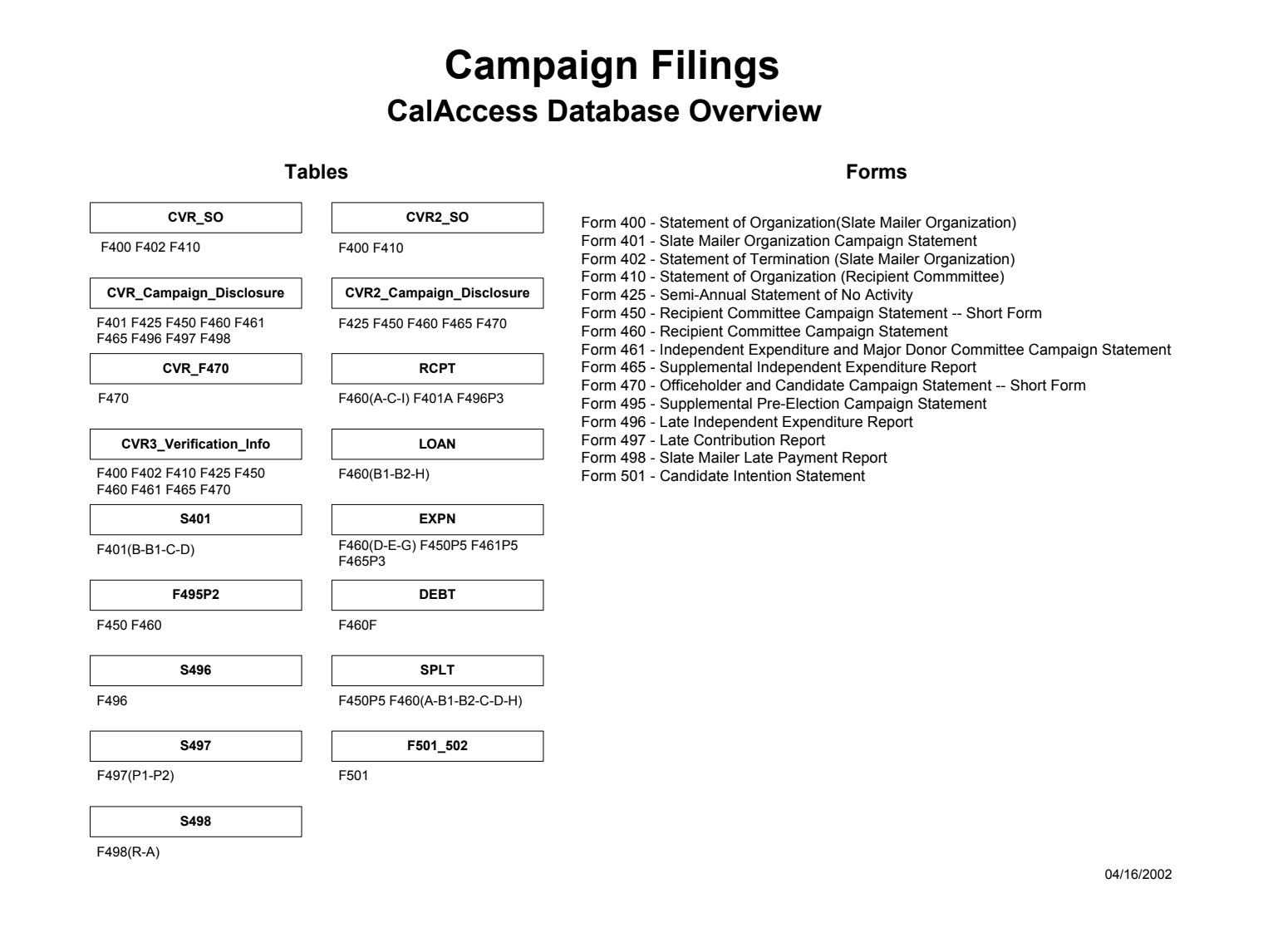

Mapping of FPPC Campaign Finance Forms to CalAccess Tables

AI fever has reached even election data, and last year a client approached me about using a Large Language Model (LLM) to allow them or any other ‘layperson’ to ask natural language questions about campaign finance at the state level in California and receive fast, comprehensive and accurate responses. Although I didn’t know it at the time, I was about to develop a great appreciation for the simple flat files that the California Civic Data Coalition created via an open source program to process the state of California’s raw campaign finance data into clean, accessible files, free of charge and available programmatically through an API.

This is because campaign finance data is an excellent example of the contextual limits LLMs often encounter. Since a comprehensive campaign finance dataset is not included in the model’s training corpus, the model isn’t able to answer questions about it, especially since LLMs are trained primarily on textual data and aren’t necessarily designed to process structured data like tables. If you want to test this yourself, ask your LLM chat agent of choice a question about the money a politician raised and where it came from, and you’ll notice quickly that unless it was written about in a news article, the LLM likely won’t have a source to draw upon.

To address this, a technique known as ‘function calling’ allows LLMs to access external data, and BLN’s DataTalk experiment is a great example of using function calling to allow an LLM to write, execute and interpret SQL queries on an external database. The downside of function calling is that each LLM model, from ChatGPT to Claude, implemented its own set of proprietary tools with differing capabilities and techniques. The next evolution of function calling, Model Context Protocol (MCP), is an open source framework published in late 2024 by Anthropic that standardizes how LLMs access external resources. With MCP, an external resource can now be exposed to any LLM model with the same MCP ‘server’ that’s freely available to any developer who wants to use it.

So that means connecting the data to an LLM was the ‘easy’ part (‘easy’ meaning ‘teams of talented engineers solved the problem for me’). The real challenge, as is so often the case with data projects, was to first acquire, clean and process a large dataset of state level campaign finance data. While federal campaign finance data is much more accessible via the OpenFEC API, California campaign finance data is notoriously difficult to access and process, since it resides in a late 90s Web 1.0 artifact, Cal-Access, made somewhat better through the Cal-Access Power Search interface, built by MapLight in 2014. Although Power Search will output .csv files, there’s no way to interact with it programmatically, and it doesn’t offer access to its raw data or underlying schema.

The CA Secretary of State (SoS) does publish raw campaign finance and lobbying activity data daily, though it’s a giant .zip file whose contents are a series of overlapping tables created from several different filing forms. Just for fun, none of this information has any data validation measures to correct misspellings, incorrect dates or other common errors filers make when submitting campaign finance disclosure forms, so it’s not uncommon to see a contribution postdated to the year 2924 or backdated to 1902. The most challenging aspect, however, is that the database tables were designed around Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC) forms rather than the objects they’re meant to describe, like contributions, candidates, committees and elections. This creates some major headaches:

Candidates and committees do have unique id numbers assigned by SoS, which are unfortunately not used as primary and foreign keys to make joining tables easy.

Contributions do not have unique identifiers to make adding new transactions to an existing database easily without duplication, and contributions that funnel money through more than one committee can be double counted when aggregating. For example, a $100 contribution to a PAC that passes the same $100 to a candidate will appear to be $200 in aggregate.

When candidates and organizations control multiple committees, this isn’t indicated in the database. Cal-Access does list committees each candidate controls, though this is in separate tables on a HTML page that need to be scraped to be useful. Cal-Access provides no information about how the several large networks of 3rd party PACs and other committees are linked.

Candidates sometimes re-use committees for multiple elections, and Cal-Access does not indicate which committee a candidate used for a particular election. This means that while we can almost always find information about a committee if we know its name or id number, it’s not always obvious which election a candidate used it to raise and spend money for.

Well aware of the many issues, SoS solicited funds from the Legislature in 2016 to replace Cal-Access by 2019. Despite spending $39.4 million out of $55.6 million appropriated between 2016 and 2022 and receiving an additional $58.7 million in appropriations between 2022 and 2026, SoS has repeatedly failed to replace Cal-Access through its long-suffering Cal-Access Replacement System (CARS), which is not expected to deploy until late 2026 at the earliest. A January 2025 Budget Letter describing CARS estimated total project cost at $92,352,324.

Although OpenSecrets also sells CA campaign finance data, its costs are prohibitive, and since it does not include SoS committee or candidate ID numbers, their data is a walled garden incompatible with public data. OpenSecrets does have a unique competitive feature with its industry labels for committees and other non-individual contributors, though in some cases upwards of ⅓ of unique entities in OpenSecrets data remain uncoded, and its labelling taxonomy could be greatly simplified. Transparency USA offers a similar product, though paying for data already created via taxpayer funds just doesn’t feel right.

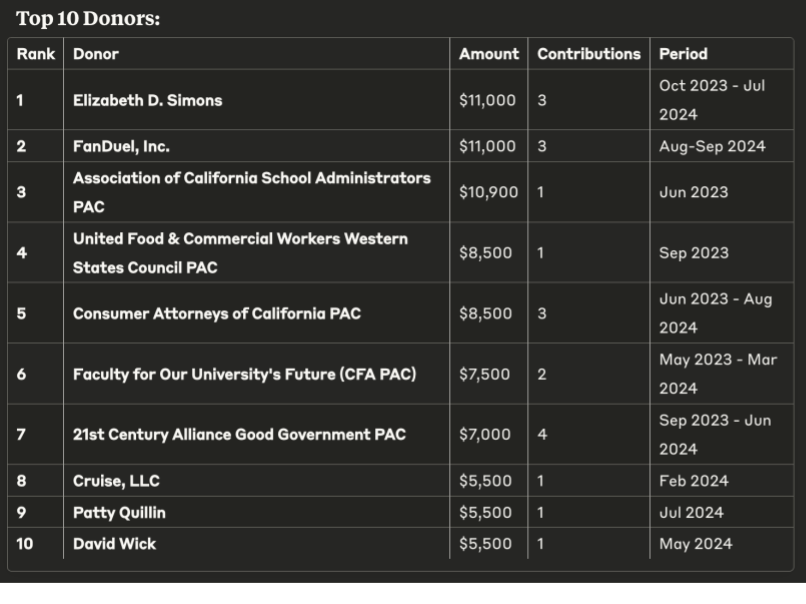

After a few months of scraping, cleaning and SQL transformations; however, we have an automated pipeline that builds a table with every monetary contribution reported on FPPC Form 460, and an open source MCP server can connect an LLM agent to this database to run queries from natural language. The table has about 12 million records, starting from the year 2000, and includes all statewide offices: Governor, Attorney General, Controller, Insurance Commissioner, Lieutenant Governor, Secretary of State and all 80 Assembly districts and 40 State Senate districts. For example, here’s the response we receive in a few seconds when we ask, “Who were the top 10 highest donors to Ben Allen this cycle?”

Sample query results for “Who were the top 10 donors to Ben Allen this cycle?”

It’s a wonderful experience, though the problem was never really about being able to ask queries in natural language. The problem was, and remains, that the data provided by the Secretary of State, and even the enriched data sold by intermediaries like OpenSecrets, just isn’t very high quality. As early as 1864, Charles Babbage, inventor of the mechanical computer (the difference engine) described this principle that has been enshrined in computer science ever since: “Garbage In, Garbage Out.”

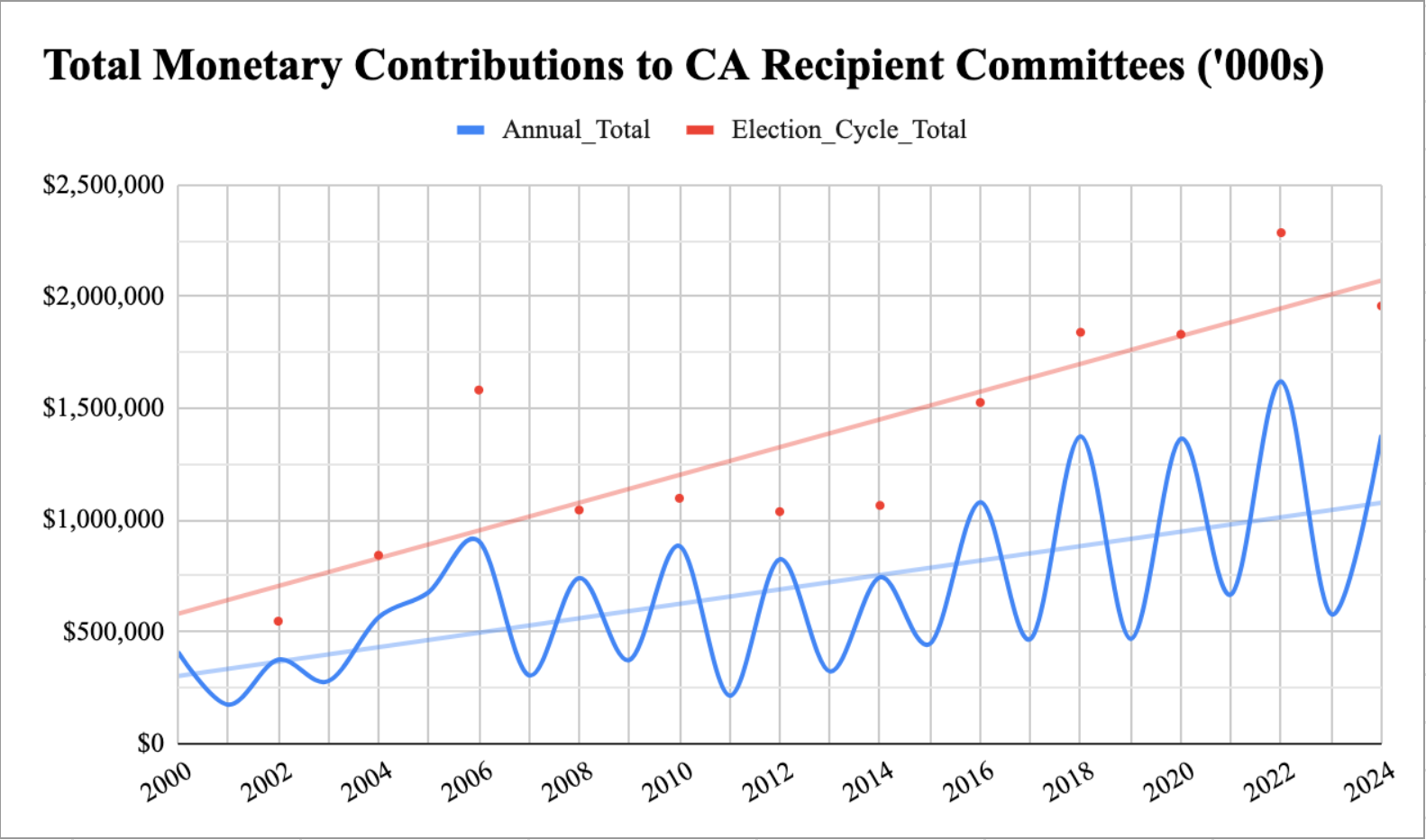

It’s vitally important to track political contributions, as elections have grown rapidly a multibillion dollar industry - and that’s just at the state level. The fact that the table below is only possible to make after ingesting, cleaning and restructuring Cal-Access’ data speaks volumes. Why should we depend on OpenSecrets or TransparencyUSA if they first have to serve a commercial market before serving citizens? Shouldn’t we as citizens, after contributing $92 million plus in tax dollars, be able to access this data without an intermediary? Perhaps when Cal-Access relaunches after the 2026 elections, we’ll be pleasantly surprised, though in the meantime hardworking open source heroes like Big Local News and the California Civic Data Coalition are selflessly picking up the slack.