Mental Health Policy in CA

Executive Summary

The Commonwealth Fund found that despite mental illness’ high prevalence in the U.S., its healthcare system compared to best in class models like the Netherlands or Germany is fragmented, inaccessible and undersized. The German system requires citizens to carry insurance and offers a public option that 86% of the population participates in. Primary care physicians do not charge a copay, are trained to deal with common behavioral health issues and can easily refer patients to specialists, while “ambulatory” psychiatrists can manage ongoing care for those with chronic conditions. While the German system is more effectively diagnosing and treating mental illness, a surge in youth conditions has spurred new efforts to provide integrated care.

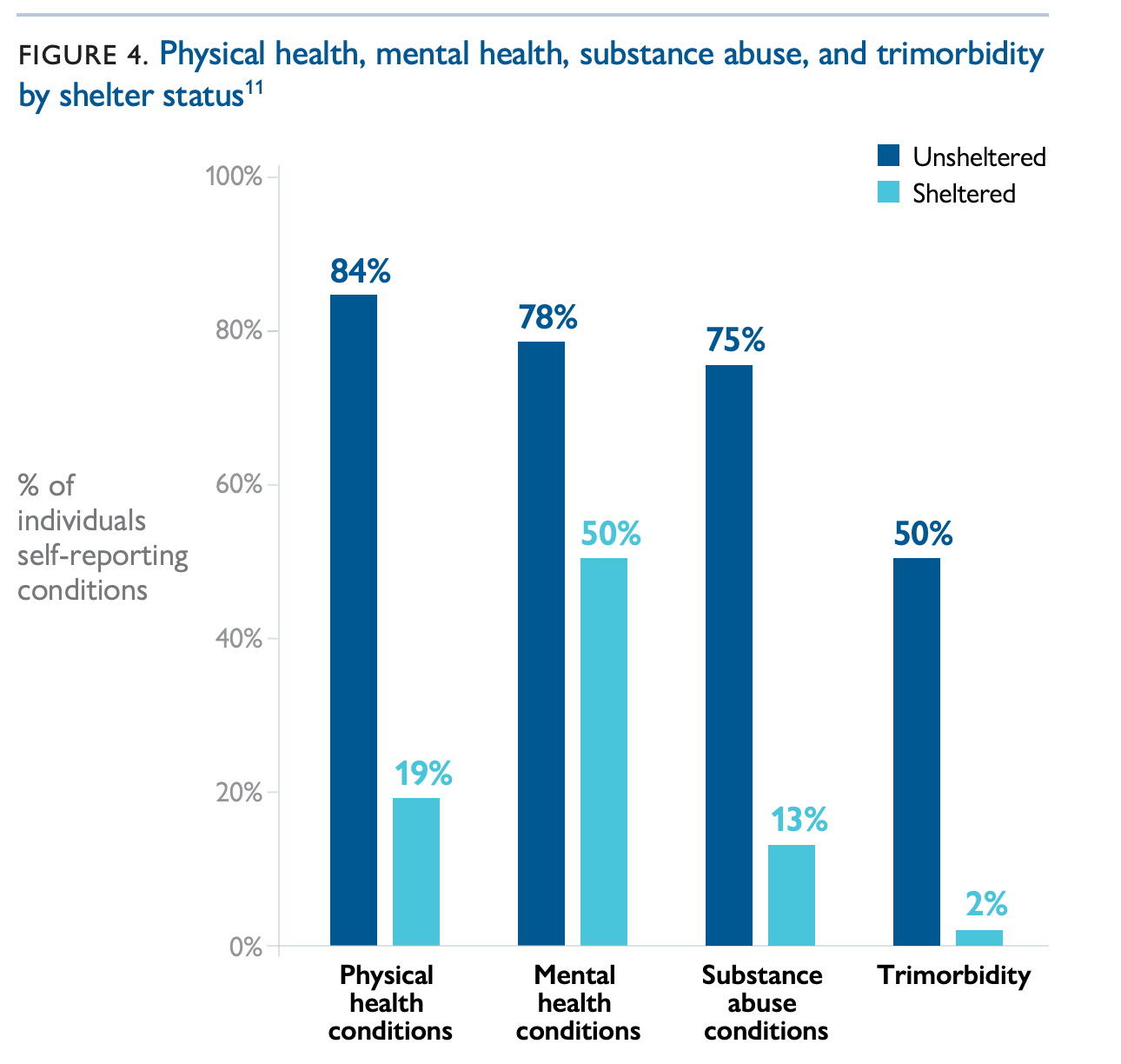

In California, where about 15% of the population, over 5 million people, suffers from mental illness, a “struggling and broken” system only manages to furnish treatment to 40% of those who need it, and 2 million mentally ill people will be jailed each year. In one sample, 78% of unsheltered homeless people in the U.S. reported a current mental health condition, and 75% reported current substance abuse.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness promotes early intervention, improved care and diversion from justice to address current gaps, and California’s 2019-20 legislative session delivered mental healthcare parity requirements to insurers (SB 855), Medi-Cal reimbursable certification for peer specialists to aid recovery from mental illness and substance use disorder (SB 803), permission for Mental Health Services Act funds to be used to treat co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder (AB 2265) and assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) as a permanent opt-out requirement for counties (AB 1976).

Governor Newsom’s CARE Court concept, passed via SB 1338, dominated the 2021-22 session, as civil liberties organizations challenged perceived coercion into treatment. In a similar vein, SB 43 expanded the definition of “gravely disabled” to include mental illness and substance use disorder to furnish treatment involuntarily. However, since CARE Court has rolled out in 8 counties since Fall 2023, very few petitions have been filed, and Newsom’s Prop 1 passed very narrowly in March 2024 to redirect MHSA funding and allocate $6.4 billion in bonds for more treatment beds to serve CARE Court’s target population. Counties may also delay SB 43 as late as 2026, and those who fall under that statute will compete for the same limited treatment resources.

Overall, California could be doing much more to provide early intervention services and divert the mentally ill from jails and prisons before their conditions deteriorate enough to be eligible for a 5150 hold, AOT, CARE Court or conservatorship.

Priority Opportunities

Explore empirical options to examine the link between housing and health outcomes to reinforce and optimize a ‘housing first’ approach at all levels

Improve accountability for all state and federal funds to counties, especially MHSA

Track AOT as it rolls out in more counties, change the law to allow court ordered medication and explicitly link those exiting incarceration, conservatorships and temporary holds to AOT and ensure counties can identify those placed on multiple holds

Secondary Opportunities

Promote and monitor medication assisted treatment (MAT) rollout in jails and prisons and require an independent evaluation of outcomes

Promote and monitor city and county level police alternative responses and possibly support additional funding if not provided in the Governor’s budget

Require school districts to implement wellness centers to deliver early mental health interventions and report on their effectiveness in line with MHSOAC recommendations

Plan and fund sufficient psychiatric hospital capacity to reduce wait time to 60 days or less

Support psychedelic legalization

Inadvisable Opportunities

Involuntary inpatient treatment, particularly in a criminal justice setting like a jail.

Jump to:

Background

According to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, those with mental illness are 4-5 times more likely to commit a crime over their lifetimes, and those with substance use disorders are at the highest risk, nearly 7 times more likely to commit crimes. In California, the number of detainees in county jails with mental illness has increased 63% since 2009, now comprising 31% of the total population, with 25% of detainees meeting the threshold of “serious psychological distress.”

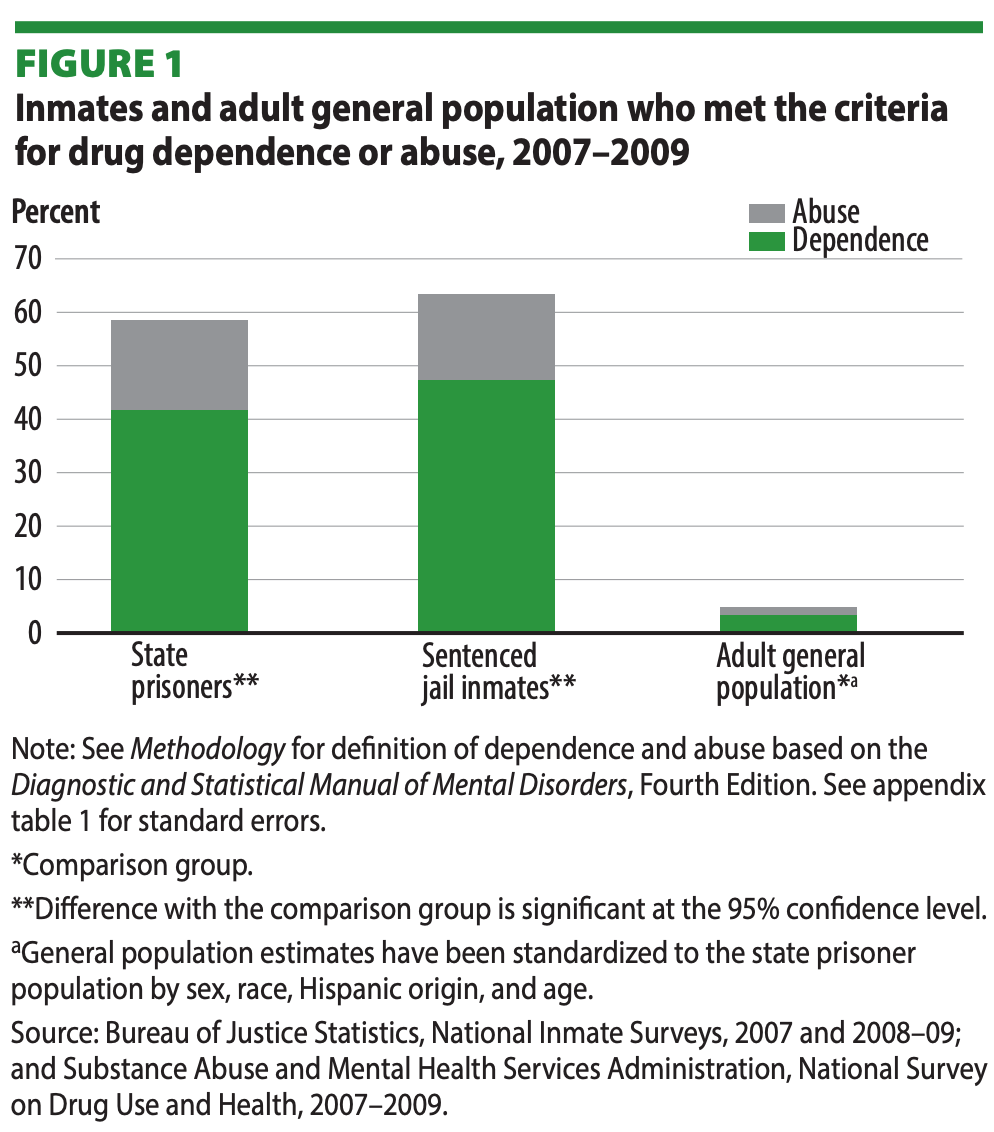

Roughly the same proportion of the CA state prison population also suffers from mental illness, and the U.S. Department of Justice has found that 58% of state prisoners and 63% of sentenced jail inmates met the criteria for drug dependence or abuse. Further, the DoJ reported that inmates who committed property crimes suffered from substance use disorders at a higher rate, 68%, than those who committed other offenses and that 39% of state prisoners and 37% of county jail inmates incarcerated for property crimes committed their offenses to get money for drugs or to obtain drugs, vs. 21% of all prison and jail inmates.

A national study released by the California Policy lab at UCLA found that 50% of unsheltered homeless individuals reported that mental illness or substance abuse contributed to losing their housing, 78% reported a current mental health condition and 75% reported current substance abuse. Another national study published in 2008 found that 9% of state and federal prisoners had been homeless in the year before arrest, a rate 4-6 times greater than the U.S. adult general population, and that these prisoners were more likely to have mental illness and/or substance use disorders. In the same year, those authors also reported that more than 15% of jail inmates were homeless in the year before arrest and that 90% of these inmates exhibited symptoms of mental illness or substance use disorder. Research has also indicated that upon release, the formerly incarcerated are at much higher risk for homelessness and that mental illness compounds this risk. Other estimates suggest that once released, former prisoners are 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general public.

The 2020 legislative session accomplished several important reforms. SB 855 now requires insurers to cover all medically necessary mental health and substance use disorder treatments. SB 803 established a statewide certification for peer support specialists who would help address the mental health worker shortage by allowing those who have “lived experience” to help with mental illness and substance use disorder recovery. The certification makes their services Medi-Cal reimbursable and brings California in line with the other 48 states who have already created this certification. AB 2265 now allows MHSA funds to be used to treat co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, which will clear the way for a substantial number of Californians to access treatment.

However, a July 2020 State Auditor’s Report on the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act implementation in LA, SF and Shasta counties found that those with serious mental illness who met the criteria for involuntary treatment would often be held multiple times and yet never connected to the “most intensive and comprehensive community-based services.” Worse, the report concluded that the state’s “disjointed and incomplete tools” require an “overhaul of mental health reporting [...],” meaning that we largely do not know the effectiveness of billions of dollars spent on 2,174 county programs each year. The report estimates that 2 million Californians suffer from serious, chronic mental illness.

Governor Newsom’s CARE Court concept, passed via SB 1338, dominated the 2021-22 session, as civil liberties organizations challenged perceived coercion into treatment. However, since CARE Court has rolled out in 8 counties since Fall 2023, very few petitions have been filed, and Newsom’s Prop 1 passed very narrowly to redirect MHSA funding and allocate $6.4 billion in bonds for more treatment beds to serve CARE Court’s target population.

In a similar vein, SB 43 expanded the definition of “gravely disabled” to include mental illness and substance use disorder to furnish treatment involuntarily. Counties may also delay SB 43 as late as 2026, and those who fall under that statute will compete for the same limited treatment resources.

Hospital Capacity

Both the California Health Care Foundation and the California Hospital Association have found that counties and the state do not have adequate inpatient beds, and the Auditor’s report noted that since statue requires state hospitals to treat patients judged incompetent to stand trial, those under LPS conservatorship outside the criminal justice system linger on the waiting list for months. The length of this waiting list has grown five fold since 2014, from 31 to 197 people in 2019 and is expected to continue growing, as 84% of the state’s roughly 6300 beds were occupied by criminal justice patients as of November 2019, and State Hospitals usually maintain a 95-97% occupancy rate. State Hospitals estimates 330 more beds are needed at an annual staffing cost of $85 million on top of $250-450 million CAPEX. The Auditor recommended that the Legislature require State Hospitals to formally report the cost to expand its facilities to address the waitlist and reduce wait times to less than 60 days. A report issued in 2022 by the CA Department of Healthcare Services (DHCS) estimated that 80% of counties did not have sufficient beds for homeless nor psychiatric treatment, and the RAND Corporation found in 2021 that California was short 5,000 psychiatric beds and 3,000 residential treatment beds, with the shortage more pronounced in San Joaquin Valley.

Although counties will also require more treatment beds, a dependable estimate will rely on better data collection, as many counties don’t have reliable estimates of current and projected capacity. As well, adopting effective intermediate treatments like assisted outpatient treatment will likely decrease demand for acute inpatient treatment.

Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT)

47 states have enacted laws to allow assisted outpatient treatment (AOT), where those who meet often stringent criteria can be compelled into treatment for severe mental illness using a court order if necessary. While implementation and results have been inconsistent state to state, increasing evidence has shown that AOT reduces incarceration, inpatient psychiatric commitment and other negative outcomes while boosting adherence to treatment.

In 1999, New York became one of the first states to enact AOT legislation with Kendra’s Law, and in 2017, the Manhattan Institute summarized the law’s impact statewide: 64% reduction in hospitalization, 71% reduction in incarceration and 68% reduction in homelessness. Despite the increased spending on AOT coordination and programming, public spending on the target population actually decreased 40%.

Although California passed AOT legislation as Laura’s Law in 2002, each county’s board of supervisors were initially only required to vote to opt into the law and identify funding to implement it. After Nevada County implemented Laura’s Law in 2008, it found that each $1 spent on AOT saved $1.81 in hospitalization and jailing costs over the first 30 months, a 45% savings of $503,061, and estimated statewide savings could have been as much as $189,491,479 over the same period. San Francisco County didn’t enact Laura’s Law until 2015; however, its three year program evaluation reported $403,614 in savings each month, an 83% reduction due to 91% of participants reducing or avoiding inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and 88% reducing or avoiding time incarcerated.

The Auditor’s report on the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act explicitly recommended expanding AOT, and Assemblymember Susan Eggman passed AB 1976 to require counties to opt-out of Laura’s Law and eliminate its original 2022 sunset provision. Counties must now offer AOT by July 1, 2021, unless they opt out, and report to the Department of Healthcare Services annually before May 1 beginning in 2022 to determine how effective AOT has been to reduce homelessness, hospitalization and law enforcement contact. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is also investing heavily in local grants to evaluate AOT, including at least $1 million to Ventura County, and these results will provide useful direction for state programs.

In more severe cases, Senator Scott Wiener’s SB 40 now allows those with serious mental illness to be placed under conservatorship without first having to undergo AOT per Laura’s Law. In 2021, Senator Susan Eggman’s SB 507 expanded the qualification criteria for court ordered AOT, and SB 43 expanded the definition of “gravely disabled” to include mental illness and substance use disorder to determine eligibility for involuntary treatment.

However, the Auditor found that only 9% of the approximately 7400 people placed on five or more 72 hour holds ($2800 to $8400 per hold) between 2015 and 2018 in LA County had been signed up for ongoing care like AOT. From 2014 to 2019, LA put 500 people on 72 hour holds who had each been put on short term holds at least 50 times previously. To close the gap between those who receive involuntary treatment and those enrolled in comprehensive care like AOT, the auditor also recommended requiring counties to dedicate MHSA funds to that end. This would include making sure the county is notified of all holds, connecting all treatment facilities to provide ongoing care and following up to ensure high risk individuals receive the care they need.

State law bars the Department of Health Care Services from any information that would reveal a name, while the CA State Department of Justice has a more complete database of those on short term holds due to being a danger to self or others in order to determine who is ineligible to possess firearms. The Auditor recommends the Legislature compel Justice to share its database with Health Care Services and require treatment facilities to report holds resulting from grave disability directly to HCS. The data should be updated daily and provided to county mental health departments in order to identify those who are subject to recurrent holds so that those who leave holds can be more effectively connected to ongoing care like AOT and the number of holds reduced.

As well, those who are leaving conservatorships may not qualify for AOT, as their condition has ostensibly stabilized in order for them to be released, even though 1/4 of them had to be placed back into more restrictive environments. Lastly, although medication is often part of AOT plans, the law does not allow court ordered medication, and the auditor recommends allowing this so long as the medication is self-administered.

Funding Accountability

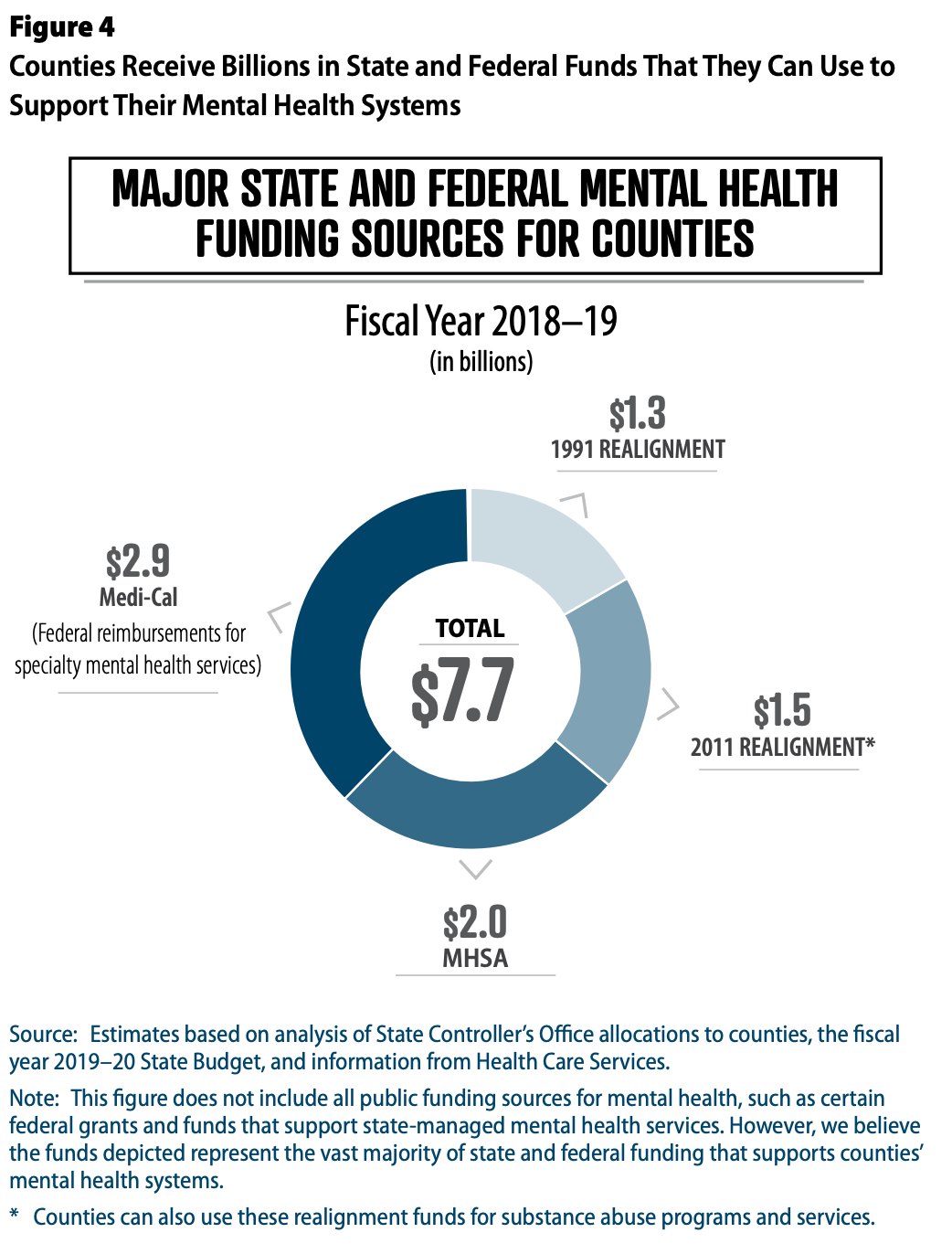

While counties received approximately $7.7 billion in state and federal funding for mental health programs over FY 2018-19, the Auditor found that public reporting fell victim to “disjointed and incomplete tools,” which prevent proper accounting of millions of dollars of unspent funds. In the three counties the Auditor examined, unspent county funds after FY 2018-19 were 73-175% of total MHSA revenues for that same period. Further, the Auditor found no clear connection between county spending and outcomes for individual recipients of those services.

The Auditor recommended that the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission (MHSOAC), which already has oversight over MHSA spending, take broader responsibility for all mental health funding by “developing, implementing and overseeing a comprehensive framework for reporting mental health spending across all major fund sources, as well as program-specific and statewide mental health outcomes.” The Auditor proposed the framework below and suggested the Legislature require counties to report to MHSOAC on these statewide outcomes annually to track progress.

hile Senator Eggman’s SB 465 passed in 2021 to require the MHSOAC to report to the Legislature on the outcomes for recipients of community mental health services in order to provide “recommendations to strengthen California’s use of full service partnerships to reduce incarceration, hospitalization, and homelessness,” it’s not clear if these reports have yet been submitted nor used for policy evaluation. Given that a February 2024 CalMatters analysis found that “more than 70% of the 1,118 reports due in the past year were not submitted to the Office of Legislative Counsel,” it is possible these reports have not been completed.

Medication assisted treatment (MAT) is a combination of behavioral treatments like cognitive behavior therapy and counseling with medications like methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone to block neurological effects and cravings. For the most part, there is little academic dispute about MAT’s effectiveness; rather, experts are focused on the best dissemination methods to increase MAT’s availability.

Research has shown that recently released inmates are 129 times more likely to die of a drug overdose than the general population and that receiving MAT during incarceration and after release can reduce this risk by 75%. Despite initial resistance, jails and prisons are beginning to implement MAT. Rhode Island was the first state to implement MAT in its jails and prisons in 2016 as well as offering it post-release, and over the first year, overdose deaths among recently released inmates dropped 60.5%. Rhode Island is also the only state known to offer all three FDA approved medications depending on individual needs.

Involuntary Treatment

Scientific evidence on involuntary commitment to substance abuse treatment programs is limited, and results are mixed. While some studies found lower recidivism and drug use, an equal number found the opposite, and the majority found essentially no difference in outcomes between voluntary and involuntary treatment.

While more than 30 states have some kind of involuntary treatment law on the books, those laws’ scope and application vary widely. Florida has one of the oldest statutes, the 1993 Marchman Act, though Tampa and Hillsborough County account for 40% of the state’s Marchman commitments, largely due to a single judge’s enthusiasm for the concept.

Marchman is a civil process where a “spouse or legal guardian, any relative, a service provider, or an adult who has direct personal knowledge of the respondent’s substance abuse impairment and his or her prior course of assessment and treatment” can petition the court to force treatment if the respondent has been placed under protective custody or an emergency admission in the previous 10 days, assessed by a “qualified professional” within 5 days, or undergone “involuntary assessment and stabilization” or “alternative involuntary admission” over the previous 12 days.

Typically law enforcement officers can admit suspects to protective custody or emergency admission for 5 days, and the same group of individuals who can petition for involuntary treatment can request a certificate for involuntary assessment and stabilization or alternative involuntary admission. The treatment could range from short to long term inpatient or outpatient, and sheriff's deputies can transport individuals to treatment if they refuse to attend. Those who continue to refuse treatment can be jailed for contempt of court.

A similar law in Massachusetts, Section 35, has been more widely used to compel inpatient treatment for several thousand individuals each year, primarily for alcohol and opiate addiction. However, the program has been more controversial given that those who have been involuntarily committed are treated much like criminals, even being housed in jails, and that these individuals have been more likely to die from overdose or other causes after release and less likely to transition into any kind of continuing care. One possible explanation for the higher death rate is that Section 35 doesn’t provide medication assisted treatment (MAT). The Massachusetts legislature is now considering recommendations from an expert panel to study and refine Section 35, including discontinuing committing individuals to jails and instituting MAT.

California’s existing statutes include a 5170 72 hour hold under the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act for “inebriates” that can be initiated by county officials and peace officers, though how often and effectively this statute is employed isn’t clear, nor is it clear if any ongoing treatment would be available from the hold. Nevertheless, SB 1227 now allows a second 30 day hold for “intensive treatment” if needed after current 15 and 30 day holds expire. Given that substance use disorder and mental illness have high comorbidity, it makes sense to integrate substance use disorder screening and treatment into assisted outpatient treatment

Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) During and After Incarceration

A county level program in New York State found that MAT participants had a 12.6% recidivism rate compared to over 40% for the jail’s general population, and there is evidence that treatment is cost-effective compared to incarceration and could reduce other costs associated with crime. A 2013 study published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment also found that released offenders who were court mandated to treatment were 10 times more likely to complete their programs and therefore less likely to reoffend. Similar marked reductions in recidivism due to substance abuse treatment both during and after incarceration have also been explicitly documented in earlier studies.

In 2016, Governor Brown wrote a 3 year CDCR MAT pilot program into the budget as section 2694.5 of the Penal Code, and by 2018 CDCR’s Receiver ordered staff to plan to roll out a “comprehensive” substance use disorder treatment program statewide that includes MAT. This memo also noted that Senator Jim Beall (SD 15) lobbied for the pilot, and the memo recognized the primary motivation was to stem the 54% increase in emergency department transports and hospitalizations and 160% increase in deaths from overdoses between 2014 and 2017, giving CDCR an overdose death rate three times greater than the national average for state prisons. Despite acknowledging that methadone and buprenorphine had better clinical outcomes treating opioid addiction, CDCR opted to offer only naltrexone during the pilot.

The pilot’s final annual report from March 19, 2019 showed that 578 inmates were referred to MAT, 497 were screened, 246 started MAT and 194 remained on MAT, meaning only 86% of referrals were screened, 49% of those accepted or were deemed appropriate for treatment and 79% of those remained on MAT. 86 individuals were released on MAT and all were linked to continuing care, though only 65 (76%) attended their first appointment. No further data on participant outcomes was available. The report also acknowledged as a lesson learned during that pilot that any statewide program would need to offer all three FDA approved medications to treat opioid addiction.

Governor Newsom’s May 2019 budget revision included $71.3 million General Fund over 2019-20 and $161.9 million ongoing General Fund beginning 2020-21 to create a statewide integrated substance use disorder treatment program across CDCR’s 35 institutions, including all three FDA approved medications for opioid addiction. The move was positively received, and in January 2020, CDCR announced the statewide rollout of the new program would begin. The program will expand CDCR by 430 positions and receive regular administrative oversight to achieve “Reductions in both SUD-related morbidity and mortality,” “Reduction in overall recidivism,” and “Improved public safety”

However, the LAO in 2019 expressed concerns that the program had not been fully evaluated, despite offering some evidence based treatments, and that the full costs and cost-effectiveness of the program were unknown. The LAO recommended, unsuccessfully, that the program be implemented more gradually, and that the CDCR and Receiver report on implementation and costs annually and have the program independently evaluated after it’s fully implemented.

At the county level, California Department of Health Care Services is implementing the California MAT Expansion Project, some 30 different projects utilizing $265 million in federal grants from SAMHSA that have brought MAT to over 21,800 individuals. This includes jails in 29 counties, though there is no long term state funding for these programs. From September 2018 to September 2019, 7381 individuals received treatment, 5144 of whom received methadone, 1806 received buprenorphine and just 431 received naltrexone. Over two years, CA MAT Expansion has reached 1646 clients in jails and drug courts.

While San Francisco was not included, the county has its own MAT program that offers buprenorphine and methadone, though its reach is limited by funds. Although David Chiu’s AB 1557 originally offered state funding to counties with substance abuse treatment programs in their jails that met certain criteria for three year pilots to expand MAT, the latest version of the bill is specifically for a state-funded pilot in San Francisco County and died in committee. The pilot would require annual reports that include the target population’s recidivism rate as well as an overall evaluation of the pilot after it expires in 3 years.

While Medi-Cal has expanded treatment availability for substance use disorders under a pilot that now reaches over 90% of Medi-Cal subscribers across 30 counties, access remains challenging for some areas, especially in criminal justice settings, and a complicated reimbursement scheme means that homeless individuals may have to wait months for an appointment they can’t pay for, despite qualifying for prescription drug coverage.

Psychedelic Assisted Therapy

While the cities of Oakland, Ann Arbor, Denver and Santa Cruz and the state of Oregon have legalized psychedelics and numerous companies have sought or received FDA approval to treat depression, anxiety, substance use disorder and PTSD with DMT (ayahuasca), mescaline (peyote), LSD, psilocybin (mushrooms), MDMA and ketamine, those substances largely remain Schedule I controlled substances. Oregon’s decriminalization measure has spurred similar calls here in CA, though Senator Wiener’s SB 519 (2022) narrowly died in the Legislature, and SB 58 (2023) was vetoed. Responding to that veto, SB 1012 (2024) proposes a stringently regulated psychedelic assisted therapy framework.

Research supports psychedelics as effective treatments for a range of widespread mental health conditions, most prominently ketamine, which is now FDA approved for treating resistant depression and anxiety. Companies researching new treatments have raised significant amounts of capital, counting on regulatory barriers continuing to collapse. Despite their potential impact, however, access will be limited by cost and insurance features, so legalization may not have any immediate effect on the most serious aspects of the state’s mental health crisis.

Mental Health Courts

Despite the large proportion of jail and prison inmates with mental illness, the current consensus is that traditional criminal justice approaches like jail, prison and probation, are ineffective wastes of resources. Mental Health Courts are a subtype of “Collaborative Justice Court” for populations with specific needs, like drug courts and homeless courts, that offer “judicial supervision with rigorously monitored rehabilitation services and treatment in lieu of detention.” The CA Justice Council as of November, 2020, counted 400 collaborative justice courts in the state, of which 53 were adult mental health courts and 11 were juvenile mental health courts. 20 counties, including LA, do not have an adult mental health court, and 47 do not have a juvenile mental health court.

In Judge Steven Manly’s Santa Clara County mental health court, roughly 70% of the 1500-2000 mentally ill defendants are treated successfully, though outcomes vary by court and county. In Sacramento County over the quarter ending September 30, 2020, 72.5% of mental health court defendants “graduated,” while the rest were ejected for not complying with the program, which includes counseling, medication and regular court proceedings. The Judicial Council reported in February 2020 that 65-75% of juvenile offenders have a diagnosable mental illness and calls for establishing more juvenile mental health courts. Research has shown better access to medication and treatment, reductions in recidivism and cost savings of $7000 per individual over 212 days compared to incarceration.

Recent reporting from Capitol Weekly described funding as a “constant source of angst” for mental health courts, as they draw varied amounts from MHSA, Medi-Cal and Medicare. While most experts and court officials agree mental health courts offer better options for defendants and cost savings for the state, there is no comprehensive state-level database to illustrate and manage these outcomes. Most of these authorities emphasize the lack of sufficient treatment facilities as well as early interventions for children and teens that could reduce caseloads in the future.

The Justice Council oversees Collaborative Justice Courts via an Advisory Committee that meets regularly and sets an annual agenda. Judge Manly is expected to present a progress report on implementing the mental health task force recommendations from 2015 on January 22, 2021 at the Council’s annual meeting, which could provide specific legislative recommendations. It may be possible, for example, to require all counties to establish both adult and juvenile mental health courts and empower the Judicial Council or another agency to collect data and report outcomes. As well, in 2018, AB 215 exempted, somewhat arbitrarily, certain offenses and mental illnesses from pretrial diversion, which will continue sending mentally ill individuals to jails and prisons which cannot treat them effectively.

Governor Newsom’s CARE Court concept, passed via SB 1338 seeks to target around 12,000 individuals with chronic mental illness with a new legal framework that would require counties to treat them. However, since CARE Court has rolled out in 8 counties since Fall 2023, very few petitions have been filed, and Newsom’s Prop 1 passed very narrowly to redirect MHSA funding and allocate $6.4 billion in bonds for more treatment beds to serve CARE Court’s target population.

Police Alternative Emergency Response

As many as 25% of people shot to death by police in the U.S. had mental health issues, and although several departments have trained their officers in social work, established “co response” models where social workers respond to calls with police or “diversion” programs that allow police to refer specific offenders to social services rather than arrest them, this year’s intense focus and criticism on police use of force has shifted to favor approaches that circumvent police entirely by dispatching teams of medical and social workers to certain calls, in many cases directly from 911.

Eugene, Oregon has partnered with the White Bird Clinic since 1989 to operate the Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) program that sends a medical worker (EMT or nurse) and a mental health worker through 911. In 2019, CAHOOTS responded to about 20% of all dispatches, and organizers estimate the approach saves $8.5 million in public safety costs and $14 million in ambulance and emergency room costs annually. CAHOOTS receives $2 million in annual funding.

While CAHOOTS is the oldest model in the U.S., several major cities are pursuing similar programs as a way of responding to civil unrest against police violence. Oakland has been inspired directly by CAHOOTS and will launch a $1.85 million pilot of its Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACRO) program as part of $14.3 million “diverted” from the OPD budget. Los Angeles is in the early exploration stage, and San Francisco and Sacramento have announced similar intentions, as has Albuquerque. Sacramento’s Community Police Review Commission recently discussed alternative 911 response models that included a presentation from a community mental health outreach organization, MH First, that started operating in January as a part of the Anti Police-Terror Project.

Since 2013, Austin’s Expanded Mobile Crisis Team (EMCOT) has responded to mental health calls, and in 2019 the program expanded to include mental health responders in the 911 dispatch center. Denver’s Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) pilot was approved in 2019 and began operating in June. Portland Street Response was also conceived in 2019, and the pilot received an additional $4.8 million to expand this Fall. Olympia’s Crisis Response Unit (CRU) launched in 2019 and costs roughly $550k annually. St. Petersburg, FL will begin dispatching social workers October 1, 2020 from the Community Assistance Liaison (CAL) team created with $3 million originally intended to hire 25 new police officers. Orlando has opted to implement a co-response program instead.

LA’s program has begun to scale up as of 2022, and a 2022 study from the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) found that the STAR program in Denver reduced reported crime by 34% while costing ¼ the amount of equivalent police services over 6 months. As one of the study’s authors noted: “[...] providing mental health support in targeted, nonviolent emergencies can result in a huge reduction in less serious crimes without increasing violent crimes,”

Rather than oppose these programs, police officials have expressed support:

Brian Marvel, president of the Peace Officers Research Association of California, said he has advocated for a decade that police should not be the primary responders to calls related to homelessness or mental health.

“Unfortunately, with city budgets and the societal ills that we face, it all gets dumped on police,” he said. “It seems to have fallen on deaf ears. But it appears now that they’re taking it seriously.”

When L.A.’s motion was introduced, Robert Harris, director of the Los Angeles Police Protective League told the L.A. Daily News his union has been discussing the idea “for a long time” and he supports the move. The union represents more than 9,000 of the LAPD’s 13,000 employees.

“For these calls that don’t necessarily need a law enforcement response, can we shift that response to somebody else?” he said.

Skinner’s SB 773 would support alternative crisis response programs by revising the 911 advisory board’s makeup to allow it to explore directing 911 calls for “mental health, homelessness, and public welfare” to the “appropriate social services agency.” Going further, Kamlager’s AB 2054 would create the Community Response Initiative to Strengthen Emergency Systems (CRISES) Act Grant Pilot Program under OES in order to establish a grantmaking process through 2024 to give at least $250k each to “community organizations in emergency response for specified vulnerable populations,” although the measure specifies no funding amount nor source. Cal Matters cited a $10 million goal, and if no funds are appropriated, the bill won’t be enacted. SB 773 failed to get out of the Assembly, and AB 2054 was vetoed.

The California Health Care Foundation, however, celebrated AB 1544 extending its 2015 slate of 13 Community Paramedicine pilots, where paramedics receive additional training to address behavioral health, provide case management for ‘frequent fliers,’ and transport clients to alternative sites like sobering centers and mental health treatment facilities. A UCSF evaluation in August 2020 found that patients experienced better outcomes while providers saw reduced costs.

Schools As Early Intervention Centers

An October 2020 report from the Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission (MHSOAC) found that ⅓ of highschoolers and ½ of LGBT students felt chronically sad and hopeless, and that ⅙ of all students and ⅓ of LGBT students had considered suicide over the past year. The report estimates that ⅕ of all children have a diagnosable mental illness (most commonly ADHD, anxiety and depression), about 1.8 million in CA, disproportionately concentrated in low-income families, those involved with the child welfare or juvenile justice systems and those who experience abuse and neglect. 50 to 75% of these children will not receive treatment or services. To reach this population, the commission recommends that the state focus efforts to make schools “centers of wellness and healing.” At the state level, this would include program development, data management, workforce development and ongoing funding.

In 2018-19, California employed 10,426 school counselors, 6,329 school psychologists, 885 school social workers and 2,720 school nurses. At the district level, this equates to 1 counselor per 626 students, 1 psychologist per 1041 students and one social worker per 7308 students. The American School Counselors Association ranks CA fifth highest for its 612 to one student to counselor ratio, well above the recommended 250 to one ratio.

The MHSA dedicates about 20% of funds ($350-400 million) for county prevention and early intervention (PEI) programs, half of which should be used on people under 25. Many of these programs do not target kids younger than 8, are fragmented across several uncoordinated organizations, have limited reach and may not be able to access Medi-Cal reimbursement if patients are not formally diagnosed. Up until LCFF was established, the state-funded Healthy Start program offered physical and mental health services to low income families through schools, and some districts continued operating these programs after state funding was phased out.

More than 3000 CA schools operate Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) that offer tiered services to students and families depending on their needs in order to reduce “punitive discipline.” In 2013, SB 82 funded mental health crisis services mostly for adults and so was amended by SB 833 in 2016 to provide “Triage Grants'' for people under 21, 50% of which MHSOAC allocated to programs for children. CAHELP JPA San Bernardino, Humboldt County, Placer County and the Tulare County Office of Education, four out of the 38 counties that applied, received these grants in 2018. The 2019-20 state budget included the Mental Health Student Services Act (MHSSA) to provide $40 million one time and $10 million recurring funding for mental health partnerships between county behavioral health departments and local education agencies. 18 counties received grants in 2020, 10 to established partnerships and 8 to newly formed partnerships. The Commission noted that requests for grant funding were “several times the available resources” and expressed its intent to work with the CA Department of Education to link education and mental health data to evaluate impact through an upcoming “data forum.”

According to EdSource, SFUSD has already created “wellness centers” at 19 schools in collaboration with city public health agencies, and LAUSD operates more than 12 of its own wellness centers.

The Sacramento County Office of Education has hired 11 family therapists and social workers to work onsite at schools and can also conduct home visits, diagnose conditions and make referrals within the county health department. Fresno county initiated a similar effort in 2017 and now staffs therapists and social workers at 107 schools, with a long term goal to have these at all 300 schools.

However, the LAO noted in its 2021 overview of school mental health spending, despite an acute rise in student mental health problems post pandemic, the state “lacks a coordinated strategy for children’s mental health,” and partnerships between schools, counties, and health plans are rare.

Safe Injection Sites and Sobering Centers

As of 2017, the American Journal of Preventive Medicine observed that while 98 “supervised injection sites” (SIS) operated in 66 cities in 10 countries (Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and Switzerland), no such site has yet opened in the U.S., except an unsanctioned experiment. This underground site found that of 100 users injecting 2574 times over 2 years, only experienced 2 overdoses, both of which were reversed, and most reported that they used the SIS site instead of a public restroom, street, park or parking lot. All syringes at the SIS were safely disposed of.

An overview of the limited research of SIS’ effectiveness found that the SIS in Vancouver decreased overdose mortality, reduced hospitalizations for skin infections from 35% of users to 9%, reduced average hospital stays from 12 days to 4, obviated a substantial number of ambulance calls and prevented HIV infections. A cost benefit analysis of the site estimated these outcomes saved $6 million per year, greater than a 5:1 ratio between benefits and costs. Another meta-analysis of studies showed that no research has found a link between SIS and increased drug use or crime, and that most demonstrated that SIS increased access to health care, including treatment for substance use disorder. Based on a Massachusetts Medical Society report, the American Medical Association formally endorsed implementing pilot SIS to examine how they can reduce costs and negative health outcomes. A Rand study concluded that we lack sufficient evidence to judge SIS overall effectiveness and that scale and cost limitations of fixed facilities could be addressed by providing mobile services while making a unique claim that Heroin Assisted Treatment, where heroin use is moderated and decrease rather than being replaced by methadone, is possibly an effective alternative.

Although Philadelphia has proposed an SIS, the U.S. DoJ has vigorously opposed it, and Seattle has allocated funds but struggled to find a site and actually open it. In 2018, Assemblymember Eggmans’ AB 186 would have allowed San Francisco to open SIS, but Governor Brown vetoed the measure citing “disadvantages [...] [that] far outweigh the possible benefits” and likely federal prosecution. Then Lieutenant Governor Newsom differed with Brown and expressed support for the concept. While a site in Philadelphia was the first to struggle with DoJ to open, several have opened in the last few months in NYC as the first in the U.S., and DoJ is re-evaluating its position on Philly's proposed site.

In a similar vein, sobering centers originally intended for alcoholics in order to divert them from emergency services and incarceration while offering an avenue towards treatment, are now being expanded to meth users. While the American College of Emergency Physicians acknowledges another dearth of evidence on patient outcomes, a 2019 cost benefit study estimated that diverting 60% of inebriates from EMS or law enforcement would save over $1.1 billion annually. In 2016, UCSF researchers proposed that the San Francisco sobering center cost about half of emergency care and has saved $3.5 million.

Housing First

While implementation, coordination and accountability at the county continuum of care level is a more pressing issue than what order treatment and housing occur, attacks on the “Housing First” approach to mental health, especially substance use disorder, have persisted. Current research indicates that offering housing first doesn't exacerbate substance use, though there are questions about what specific treatment approaches are more effective to address substance use and mental health disorders once a person is housed.

Generally we already know that people require more than just housing, and that providing this housing is a good first step to linking them to further treatment and services. For example, Dr. Jack Tsai and colleagues found in their 2011 study, Does Active Substance Use at Housing Entry Impair Outcomes in Supported Housing for Chronically Homeless Persons?, that although housing did not improve their substance use disorders, neither did they worsen. A 2010 study by the same team, A multi-site comparison of supported housing for chronically homeless adults: “Housing first” versus “residential treatment first”, found no clear benefit to requiring transitional or residential treatment before housing.

Another 2011 study, Substance Use Outcomes Among Homeless Clients with Serious Mental Illness: Comparing Housing First with Treatment First Programs, found that those offered housing first used or abused substances less than those offered treatment first; in short, that “Housing First clients are more likely to stay engaged in a program and be residentially stable” because “having the security of a place to live appears to afford greater opportunities and motivation to control substance use when compared to the available alternatives of congregate residential treatment or a return to the streets.” On the other hand, a 2022 study, Housing Outcomes of Adults Who Were Homeless at Admission to Substance Use Disorder Treatment Programs Nationwide, found that most homeless people who undergo treatment remain homeless even after treatment.

Moreover, a 2012 study, Housing First for Severely Mentally Ill Homeless Methadone Patients, found that those who were housed were nearly twice as likely to receive substance use disorder treatment than those still unhoused. A 2015 study, the impact of a Housing First randomized controlled trial on substance use problems among homeless individuals with mental illness, found that those offered housing first significantly reduced their alcohol use compared to the treatment group, though there was no significant difference in other drug use.

As the Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH) posits:

The federal and State government recognize Housing First as an evidence-based practice. In fact, a settled and growing body of evidence demonstrates—

Tenants accessing Housing First programs are able to move into housing faster than programs offering a more traditional approach.

Tenants using Housing First programs stay housed longer and more stably than other programs.

Over 90% of tenants accessing Housing First programs are able to retain housing stability.

In general, tenants using Housing First programs access services more often, have a greater sense of choice and autonomy, and are far less costly to public systems than tenants of other programs.